Feature on Lucka Ngo published in print April 7, 2017

(There were errors in the text published in print, please see digital version for the corrected text. Volume 5, releasing in June 2017, will publish a corrections note in print)

She refused to stand still when the world did not. No customers had walked in to Pho Sure on West 4th street in New York City for the past hour and so, Lucka Ngo took a seat. The split ends plaguing her jet black hair provided no entertainment and the crumpled dollars in the tip jar yielded to pizza for dinner, again. Idleness was not a language Lucka spoke and she spoke four of them, English, Czech, Vietnamese and some Spanish. The restaurant was small, four booths seating four plus people and six tables for two. During the week she worked alone letting the smells of basil, Saigon cinnamon and lemongrass carry her home.

Depending on how she decided to answer that day, Lucka’s home was between 4,094 (Czech) and 8,644 (Vietnam) miles away. This was a job to some but for Lucka, this was a way to pay the bills. When people ask her what she does for a living, her response was usually, “I take photos.” Lucka, 21, like those she shares the city with, was already someone, whether you knew it or not. An FIT student studying business management, Lucka’s self-taught photography has gotten her gigs with brands like Stussy, Urban Outfitters, High Snobiety, King Kong Magazine, L’Officiel Italia and Hypebeast, but this is not a fairy tale.

A friend once told me that New York was home to people who didn’t have one. They flocked from all corners of the world to a place dubbed, “the city of dreams” to make something, anything happen because here, everything was possible. It was a beacon of hope, a storied tale of surreal successes and cursory failures, its bright lights promised sunrise at sunset. It’s a beautiful cliche best viewed in hindsight when you, like Lucka, can say, “before New York, I wasn’t shit.”

Vietnamese by blood, Lucka grew up in the Czech Republic on the border of Germany in a small town called Cheb. Her parents moved from a small village in the north of Vietnam to pursue better business opportunities for their wholesale operation, they sold lighters. The Vietnamese people represent the largest immigrant community in Czech but big numbers don’t equal assimilation. Lucka’s parents never picked up the language leaving her and her older brother, Duk, to navigate the space between two intersectional cultures.

She was eight or nine when she watched her brother pack his bags, kiss their mother on the forehead, embrace their father with two, strong arms and wave goodbye as he left for America. Growing up, they had shared the same English tutor. Dreams were a topic that came up often and America was their genesis. The one way ticket to New York that her brother flaunted marked him for nameless success even though he flew there on the wings of an empty promise. She fell asleep at night thinking of him, hoping that Lady Liberty’s love wasn’t always unrequited.

Moving fluidly between cultures daily, Lucka spoke Czech in school and would come home to Vietnamese traditions and her native tongue. Home was never a place, nor was it cultural comfort, the coordinates of which were dictated by her blood at 14.0583° N, 108.2772° E. Closing her eyes she can hear her parents whisper the words, “don’t forget who you really are.” Yet multiplicity was a blessing as it grounded her while giving her room to grow. “Me and my peers would always be called, ‘bananas’. The skin is yellow but when you peel it off, it’s white inside. It’s like we weren’t sure of our own identity being Asian but most or some of our behaviors, manners, food, traditions would be Czech,” Lucka explained over email. But the reinforcement of her Vietnamese roots left no room to ponder identity or ask if she belonged. “That kind of question actually never came to my mind. Every time someone asks me I say, I was born and raised in Czech but I’m Vietnamese. That’s all I would say.” When Duk returned from America to visit for the first time, he brought with him more than hope. He brought a Canon EOS Rebel T2i which she would make hers. It was nothing serious, just a way to capture moments, scan memories and fan through emotion. The sense of permanence that photography offered was necessary for someone who waxed and waned with the moon as she did.

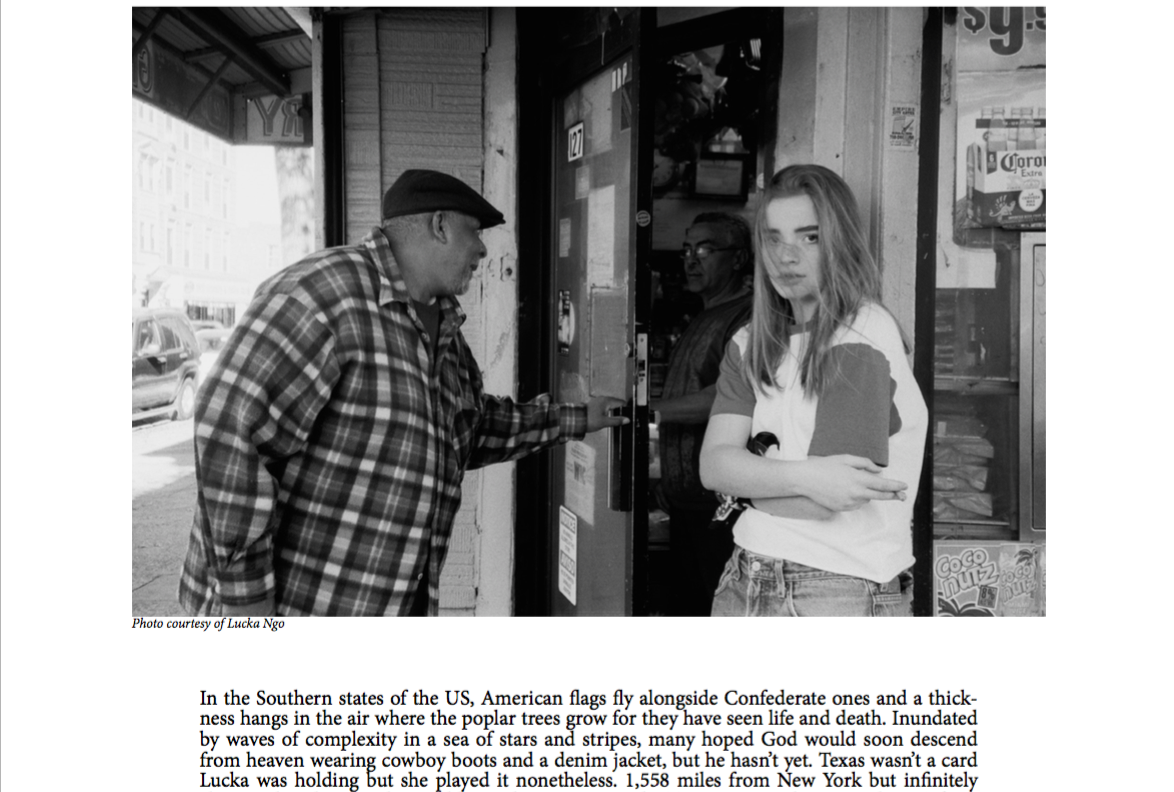

In the Southern states of the US, American flags fly alongside Confederate ones and a thickness hangs in the air where the poplar trees grow for they have seen life and death. Inundated by waves of complexity in a sea of stars and stripes, many hoped God would soon descend from heaven wearing cowboy boots and a denim jacket, but he hasn’t yet. Texas wasn’t a card Lucka was holding but she played it nonetheless. 1,558 miles from New York but infinitely closer to her dreams, she would spend a year in Laredo, Texas as an exchange student. A family had picked her out out of a photo album of agency-hosted hopefuls granting her access to the American Dream. The host family no habla inglés, but their daughter, Adriana, did. She turned a language barrier into a bridge between the two worlds. “It was a total shock to be away from my parents for the first time because I was so attached to them but I had no choice other than to adapt,” said Lucka breezily. She went to church every Sunday, experienced a “quince” (a traditional, Spanish 15th birthday party) and went to high school with students from around the world. She wasn’t supposed to talk to her family more than once a week in order to reinforce her English, but her connection could never be severed despite the distance.

Graduation lay visible on Lucka’s horizon but there was no silver lining. American’s graduate from high-school in the 12th grade but in Czech, it was the 13th. A GED was her only ticket to college and the winds blew her westward to the California coast before whisking her away to the big apple to attain a college degree. She didn’t know where she was gonna go to school but Google had the answer, “I just knew I liked fashion so I just typed in fashion and then FIT came up.” Hello, West 27th Street.

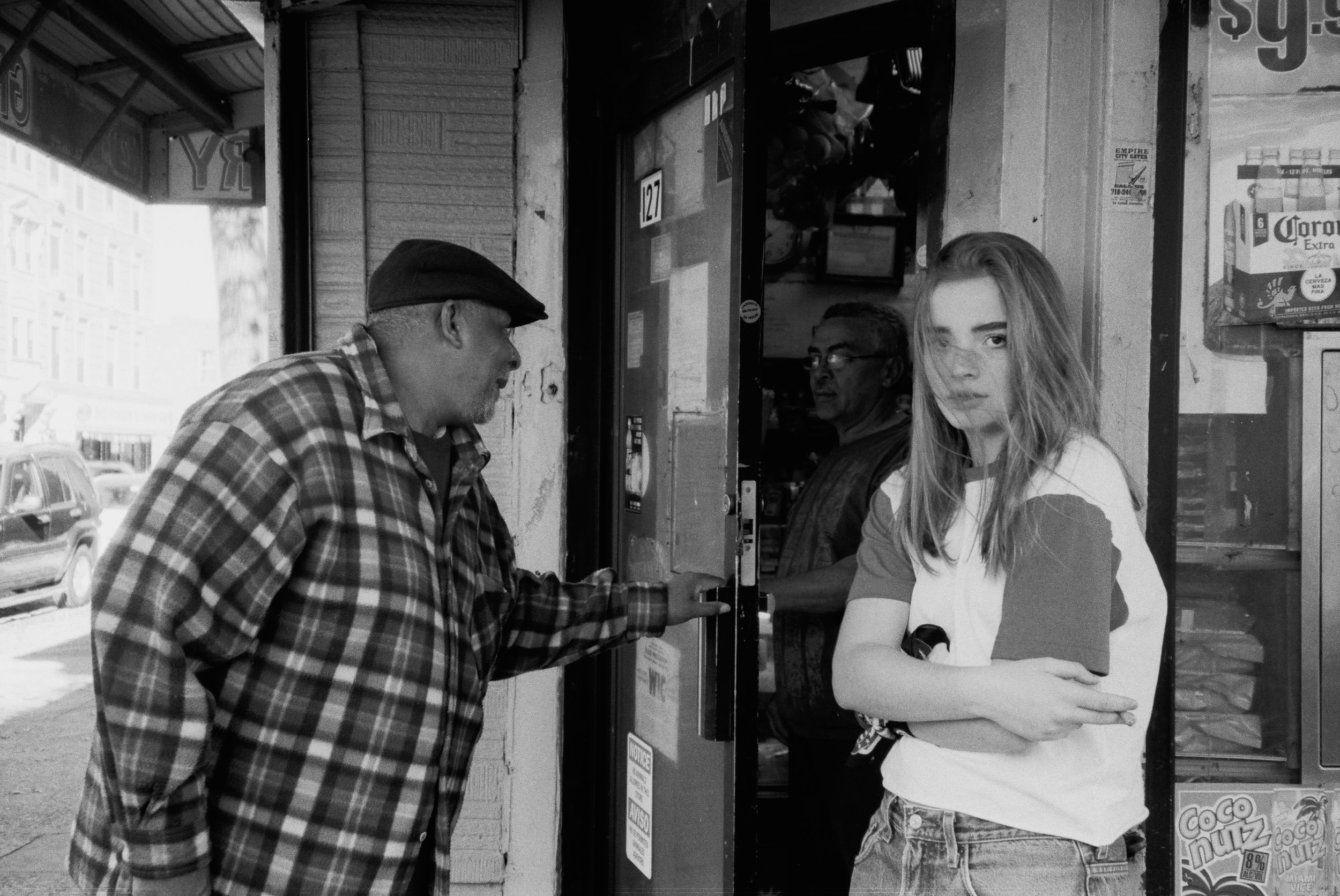

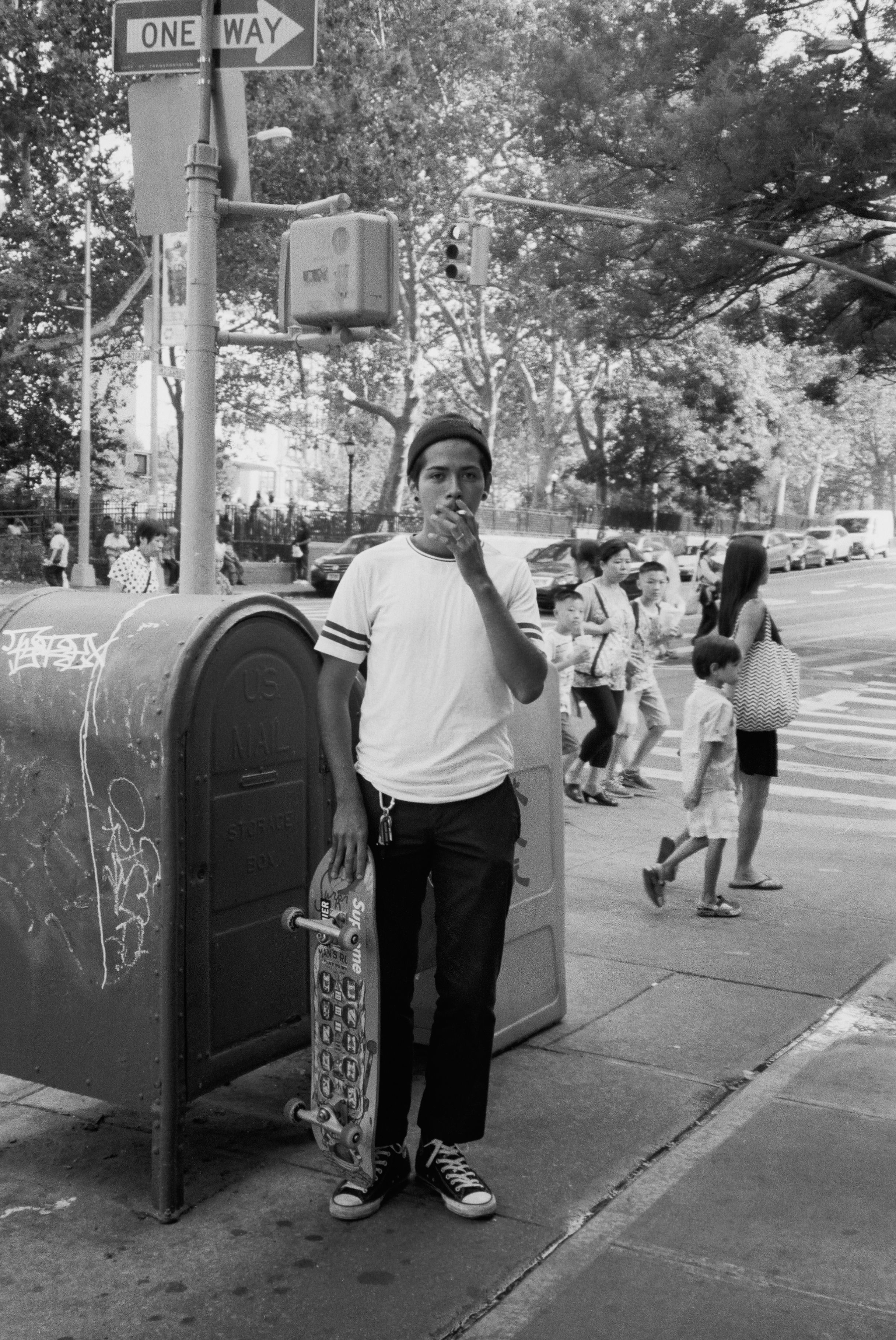

Her first impression of New York was that it was “mean”, her frame of reference of course was public transit. “In San Francisco, when someone bumps into you on the train, they’ll be like, ‘oh sorry, are you okay?’ But here in New York, they bump into you and they’re asking for an apology.” She arrived at a time in her life where she still described herself as “shy”, “insecure” and “innocent.” “When I was back home, I’m not saying that I was nobody, but I was hiding myself, asking like what am I talented at? My friends were talented at singing, I would sing too but I wasn’t that good. My other friends would be good at this and that and I wondered what my talent was. New York totally opened me up. There I was, arriving to a place where everyone is so confident and all these people were like, you have to be confident in order to be successful,” said Lucka. Photography was the first thing that she had felt sanguine about and the streets of the city teemed with eccentricity and emotion, encouraging her to click the shutter time and time again. Deciding to major in business was at first an act of fear but it gave Lucka the knowledge that would give freelancing enough palpability to pay for half of her expenses, but let’s not get too far ahead of ourselves.

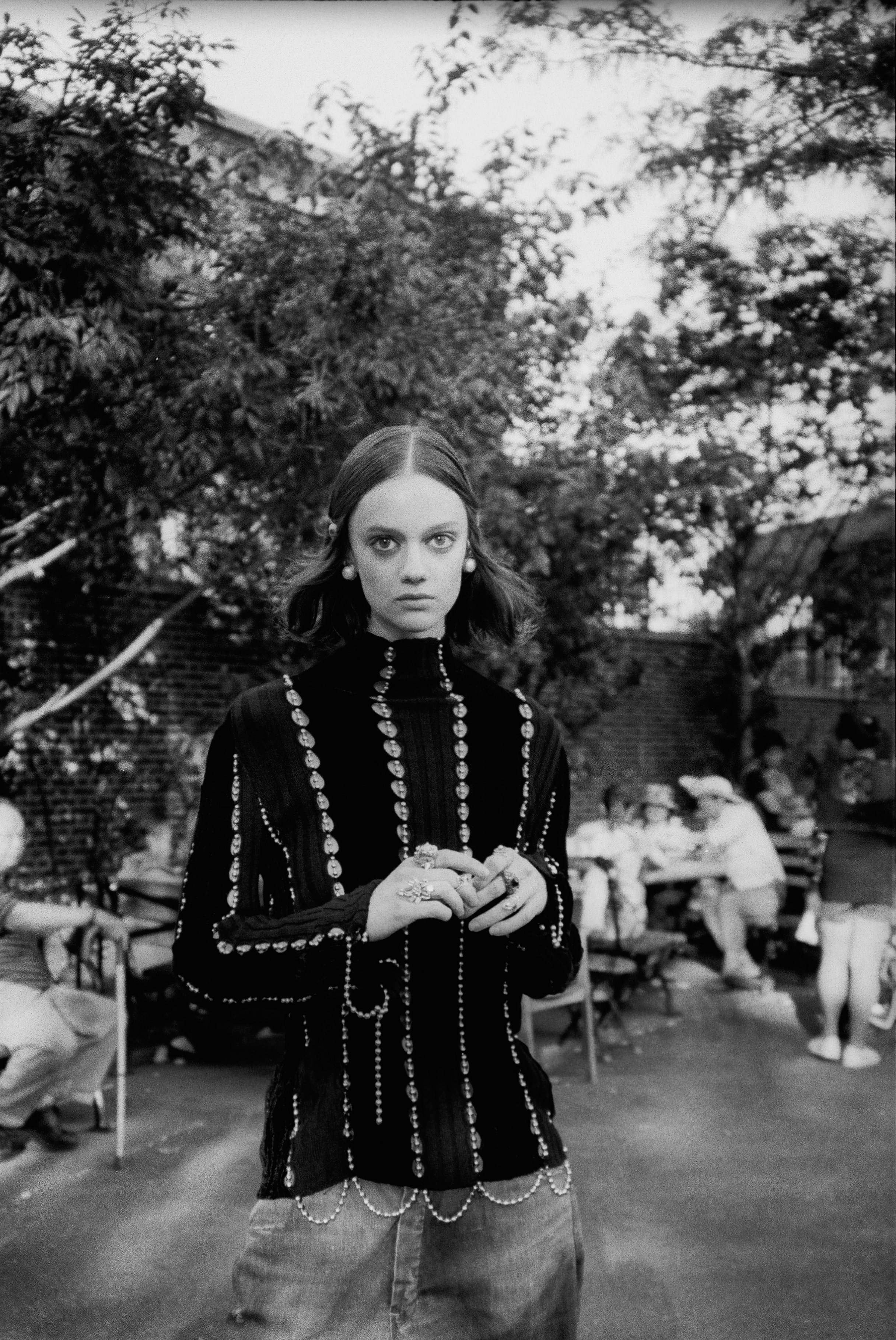

When Lucka looked at her photographs she never saw a career lying beneath the grain. Realness is what she aimed to capture and being “photogenic” was a quality gauged by feeling and friendship. Lucka’s background defines her aesthetic, she’s moved around so much that what holds her attention moves her to feel something, therefore, making it meaningful. It wasn’t until she turned a hobby into a potential career that she began to doubt herself. “So many people I felt like damn, that guy has a nice camera, they take such good photos, oh I ain’t shit. I was putting myself down a lot but I still kept going, kept shooting, I would shoot whoever wanted to shoot, I would shoot them even it was raining,” said Lucka. Members of her family passed judgment via what popped up on Facebook KJFHDSJKFH. Aside from her father, they were worried that she would make a fool out of herself, A.K.A broke. Yet, pleasing people was not a measure for progression and in a city of over 8 million people, imitation was not a form of flattery, it was instead the quickest way to never standing out. Judging by the cornrows and heavily-winged eyeliner Lucka now sports, she’s figured that out and in turn, found herself in the process.

As millennials we are often called lazy, narcissistic, nothing but dreamers pining for jobs that make us happy despite not always being able to pay our rent without sacrificing actual food for packaged ramen noodles. Yet our generation, starry eyed, iPhone in hand, wielding “privilege”, understands and expects opportunity to be democratic. Through the likes of LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram DM’s and with a little initiative and ambition, we’re able to showcase our work, get famous before we get rich and contact just about anyone who wants to be found. Most of the jobs that Lucka receives are from the photos she posts on Instagram, “but it’s also me reaching out to the main people right away. That’s what I really like,” she says of this new work model, “If I’m reaching out to a really important person from a brand or a designer, I want to reach out to them by myself, straight up to them. I don’t want to go through this person, that person.” A teacher once told her, “every no is a step closer to a yes.”

Sprinkled with bouts of reinforced concepts of self-love and panic attacks, rejection has taken on a whole new meaning. It can take the form of an unaccepted friend request, a magazine hiring Gigi Hadid over an aspiring photojournalist to cover fashion week, or internships that don’t pay and don’t result in a job. Sound familiar? “The individual today is in a constant need of affirmation.” Yet, we, like Lucka grew up harboring a unique capacity for empathy, and creativity is the last frontier for its expression. We are only bound to the struggle if we look anywhere but in the mirror to see that, we, are the future. This is not just Lucka’s story, this is our story told through the lens of a friend, in the voice of someone who speaks a language we can all understand: dreams.