Ray of Carnage NYC: Documenting the living history of graffiti through zines

The buff. Taking the form of paint itself, a kind of chemical bath or hired cleaners wielding mops, graffiti, which first hissed and misted its way from top to bottom onto New York’s subway cars in the 1970s, finally had a war on its hands. The year was 1985 and the city of New York shelled out 14 million dollars which would be allocated towards the “Clean Train Movement” cleaning up the fades, burners, pieces and floaters that meant you were “up” in the graffiti world, a step closer to fame, to becoming an “all-city king”. Lingering on the Subway platforms as those before them had done, they would watch… wait… with arms crossed as scads of commuters moved through the station in waves, from closing doors to flights of stairs whose byways would surface amidst bodegas and a sea of pavement, searching… for their spray-painted names riding their line clattering by at speeds of 30 miles per hour. For “writers”, what the world calls “graffiti artists”, this fabled tradition known as “benching” was once redemption. It now left them unslaked and empty.

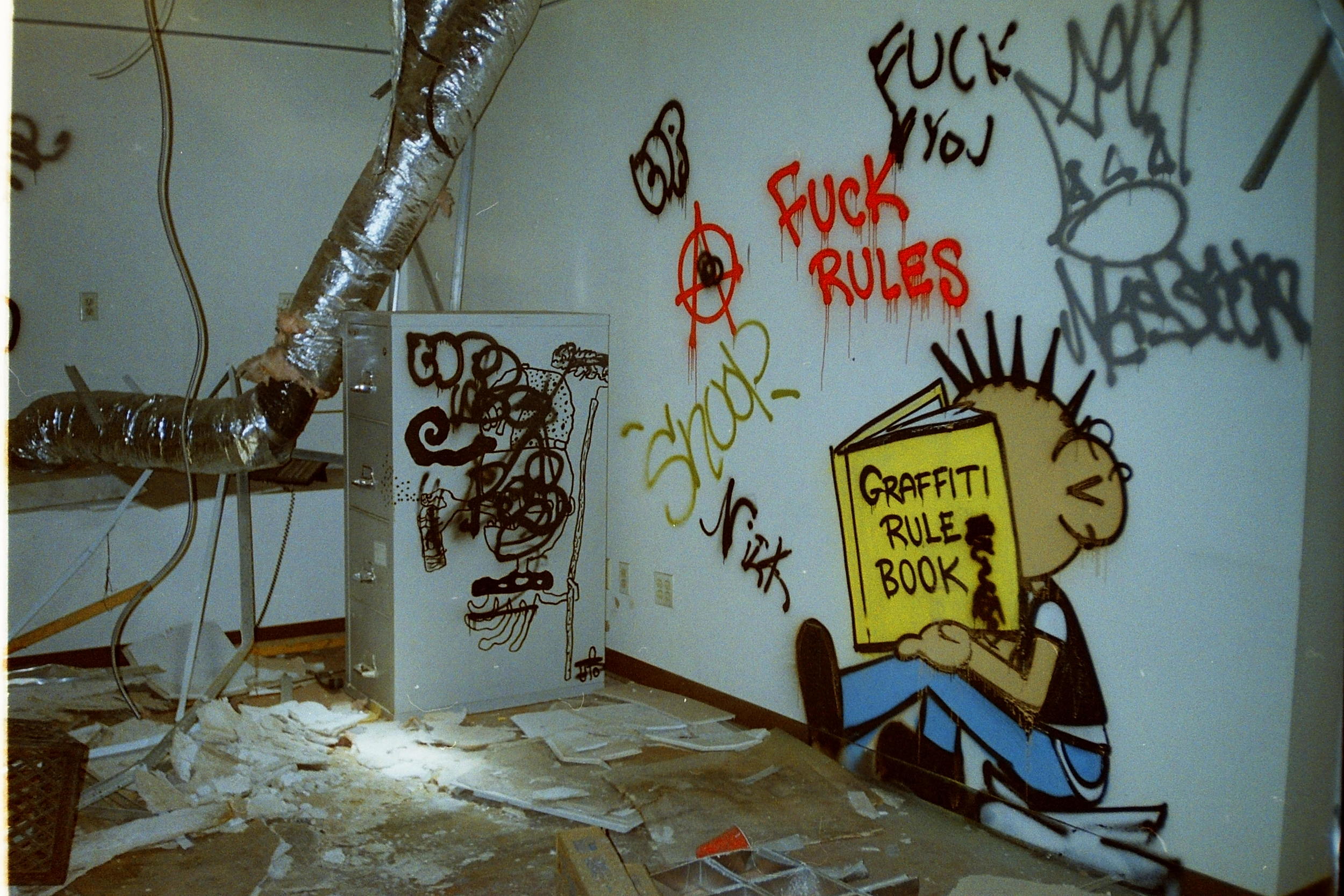

From climbing barbed-wire fences, outrunning the NYPD and waking up to paint in the train yards or on elevated tracks 40 feet high as club-goers called it a night, the era of subway graffiti was ending (at least for now). Some writers resorted to a familiar but lesser thrill in the scrap yards as the MTA began a mass retirement of its flat cars, marking them for destruction. Others changed with the times; with the rise of hip-hop and a flavor born and refined by the streets, with the laws that would make the act of writing a felony and with the “street art festivals” that would create a vomit inducing love for graffiti in the hearts of New-Yorker wannabes. Call it “fame” or call it “infamy”, this notoriety, achievable only through fat caps, “bombing”, “throwing up” wherever possible and the recognition that came from the head-nods of a select few, lingered. It took the highways first, moving to rooftops, to the walls of all five boroughs, it reinvented itself. It took the form of the acid etchings that many shrugged their shoulders at, it was found hanging on the walls of the MoMa and other museums, thus manifesting what renown writer, Crash, called “the last stop on the subway line” (Ehrlich).

We still see it, the graffiti; what many today consider to be synonymous with Banksy. We have the Obey Giant shirts, see it on the back of bathroom doors in dive bars and restaurants and Pow!Wow! Hawaii invites artists to our home to paint our walls so we can take “artsy pics” but this isn’t all just history book material yet. The history of graffiti is still writing itself.

In a concrete jungle where skyscrapers were their own horizon, Ray Mock, a German guy with a noticeable accent and a sleeve snaking around his left arm, soon found the value in a good pair of shoes and his camera when he first moved to the city in 1998. Since then he has founded Carnage NYC, an independent publishing company dedicated to preserving and documenting the living history of graffiti since it came up from under, literally. “I started by shooting street art because it was an easy in. The most active New York street artists, such as Swoon, Faile or Bast, weren’t super well known at the time and there was no such thing as Instagram yet. You could still walk around and discover things on your own, and shooting street art was a good excuse to get out of the house and discover the city. The more I did that, the more I started noticing tags, liking specific handstyles and recognizing names. It was like going down a crazy rabbit hole,” he said from his Brooklyn office near the Navy Yard this past spring.

Backtracking. The miles walked, countless clicks of the shutter, internal moments of “awe” and excitement that came with discovering a sick piece down a decrepit alley originally amounted to Ray uploading his shots to Flickr. While having an online gallery filled with .jpg’s and works of those nightcrawlers outfitted in black, armed with palettes of spray paint, was somewhat fulfilling, Ray missed something that he could hold in his hands, something that was more carefully curated. The first Carnage zine, Grilled I, came out in 2010. The issue featured the doors of New York City. Those plastered with tags, those that residents had tried to paint over countless times before, those defaced impulsively courtesy of drunk passerby’s with sharpies and those graced with something real, something special, something that could be deemed art even if the paint or pens were racked. That was the beginning.

The alarm on a Monday morning would go off once before it was told to snooze for another ten minutes. Coffee was made and the commute by subway was made to an office that seemed more dimly lit than it was solely because Ray’s mind wasn’t fully there. Before working on Carnage full time, he was an internet product and project manager. “During lunch breaks I would go take photos or drop off a bag of zines at the post office. That’s all I was thinking about and all I wanted to work on when I got home in the evening and into the wee hours of the morning. It took me a while, but eventually I realized that this was what I needed to be doing full time,” Ray said. Bit by bit he was pulled further down the rabbit hole. There, he found that this hobby of zine-making was something harder to get away from as there was a need to do the work of these writers, justice. Subsequent issues of Carnage have featured the works of Kuma, Lush, MAYHEM Crew, Hert, Atak and many other legendary figures in this illicit world.

So how does Carnage work exactly? What goes into making one of these zines? Well, for starters, Ray makes contact with these artists somehow. The main thing, he says, is trust. Ray doesn’t ask their names, where they live, if they have a criminal record or any other personal information. What’s important is their work, what they write and where and how they write it. The very essence of graffiti is that it is illegal, it’s the willful destruction of property; that being said, much of it is temporary and its purveyors have to remain anonymous, their identities can’t be revealed though the masses have seen their work. The nature of the latter is where people like Ray come in, he speaks of this “symbiotic relationship between photographers and writers” where both parties work to perpetuate the existence of a piece that was buffed etc. The fact of the matter is, whether graffiti is a craft or an art-form, writers have an interest in preserving and showcasing different facets of their work. “Once people buy into the idea of collaborating on a zine, they’re willing to share and open up their archives. That’s another motivation for me. So many people lose their archives because they have to throw them away or they get raided (by the police), so I think there is something to be said for trying to preserve some of that material in some form,” Ray said. Once the vision for an issue was set, Ray then becomes a creative project manager of sorts, as he tries to get all the material to form a coherent, visual story that allows readers to get to know the artist, their work, where they’re coming from and where they’re going. “Even though it’s not my artwork and the photos aren’t necessarily all mine, I feel like there’s a little bit of me in those zines as well, an aesthetic vision” Ray said.

Although these issues are printed in limited copies, sold online at http://carnagenyc.bigcartel.com and the Instagram account has 37.5k followers, this doesn’t mean that the war graffiti was fighting years ago is over. A new saboteurhas risen and the masses have mistaken it as graffiti, for them to be one in the same. The saboteur we speak of is “street art”, murals, legal art. The problem with getting these two entities mixed up is that it seemingly overwrites the history and disrespects the legacy of graffiti with something that is of a different mentality which often opens the door to gentrifiers in neighborhoods where hipsters don't necessarily belong. These worlds inevitably collide and the hostility visibly manifests in hot-tempered throw-ups over freshly painted murals that someone had paid hundreds of dollars to commission. Ray spoke out about this even though he has no personal stake in the conflict, “there are still people (graffiti writers) who took a little bit of a risk and made things not for profit or anything. I think that’s changed a lot just because there’s actually a market for so much of that art now and it’s been commodified so much and that’s propelled animosity between artists, between different groups and it made it a little harder for me to like all that street art stuff. More power to them (street artists) for having gotten to the point where someone pays them to fly there and paint a wall, it’s awesome but there’s a certain homogenization of that kind of culture. You can’t pin gentrification on a few murals per se but it leaves a bad taste in the mouth for a good reason.”

Walking around the vicinity of Ray’s studio with him, he carried his camera around his neck and a navy blue WESC hat sat perched on his head. He pointed and read aloud the names of seemingly illegible tags with ease and stopped to snap a few photos of a few throw-ups and pieces sneeringly adorning a few box trucks. What might appear to most as something a pubescent, city kid does as a result of getting caught hopping the Subway turnstile and thus wants to rebel, actually is so much more than that. Graffiti as Ray and those on the inside know, it is its own language, it’s an ongoing dialogue with the city and its residents, it’s an experience to be had that takes confidence, drive and balls. “Graffiti, by its ephemeral nature, is reliant on oral storytelling because so much of it doesn’t get recorded or filmed or written down in any sort of meaningful, cohesive way. It’s definitely a privilege to hear those stories from writers who have been part of modern graffiti history and to be able to record and share some of them,” Ray said. Through Carnage NYC, Ray has thus opened up a little bit of this dialogue so that you and I and anyone with eyes and not too much of a stick up their ass can begin to become aware of this conversation, if not a part of it. Pick your eyes up and let the walls do the talking.